The “Green Book,” which helped African Americans navigate a segregated country, has been almost fully digitized.

Black travelers came up with innovative solutions to sidestep humiliation (or worse) on their journeys, such as wearing turbans. One of these creative ideas was conceived by Harlem postal worker Victor Hugo Green. To help black people plan a safe route across the minefield of discrimination in the U.S., he started publishing guides called the Negro Motorist Green Book in 1936.

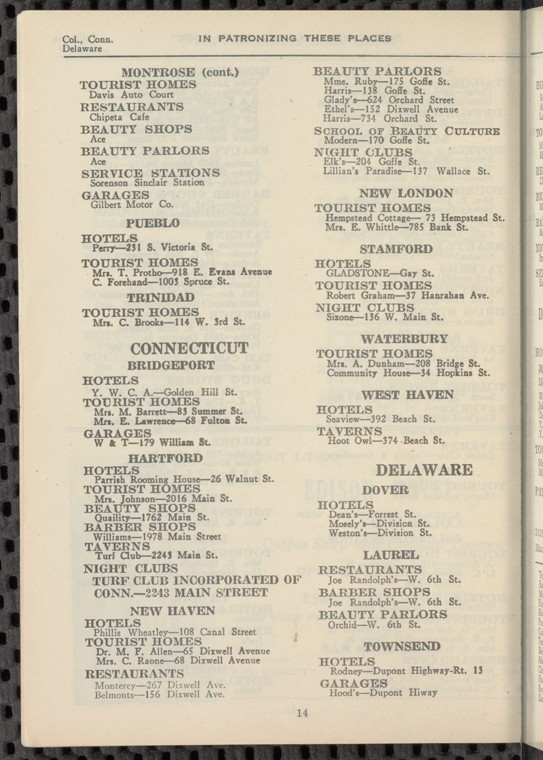

The Green Book, as it came to be called, listed where African Americans could stay and eat, and what businesses would serve them, across the nation. The first issue only covered the New York metropolitan area, but subsequent ones covered the entire U.S. and even some countries abroad. This year, almost all of these guides, published between 1936 and 1966, were digitized by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library.

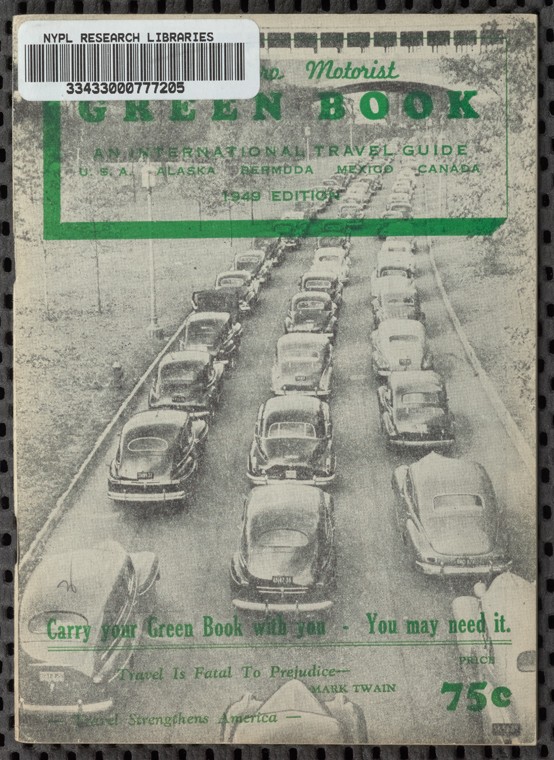

Here’s Green explaining the intent and inspiration behind the guides, in the introduction to the 80-page 1949 issue:

With the introduction of this travel guide in 1936, it has been our idea to give the Negro traveler information that will keep him from running into difficulties, embarrassments and to make his trips more enjoyable. The Jewish press has long published information about places that are restricted and there are numerous publications that give the gentile whites all kinds of information.Here’s the cover of that issue with a quote by Mark Twain (“Travel is fatal to prejudice”), followed by some of the listings inside:

Well, when I - my family had a "Green Book" when I was young, and used it to travel in the South to find out where we could stop to eat, where we could spend the night in a hotel or somebody's home. And I always thought it was called the "Green Book" because it was green.For contemporary writer Calvin Alexander Ramsey, the books have been an inspiration. He’s has written a play and a children’s book about the experience of traveling using the Green’s guide during the 20th century. Now, he’s working on a documentary called The Green Book Chronicles. In a recent interview with The New York Times, Ramsey said the book was literally “a life saver” for African Americans back in the day.

”There are still issues with ‘driving while black,’ but nothing like it used to be,” he said.

Green ceased publication of his guides following the 1964 Civil Rights Act, assuming there would be no need for it. Here’s how he imagined the future in the 1949 guide intro:

There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide may not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States.That day, unfortunately, is not yet here. Driving while black can still lead to an arrest, and in some cases to death. Swimming pools and classrooms aren't safe from race-fueled violence. Local businesses still treat black customers like second-class citizens—even in Green's own Harlem. Maybe some sort of 2015 update to Green's guide would be useful after all.

No comments:

Post a Comment